On one level, Jan Vermeer fits comfortably in the classification as a “little Dutch” master. He works in the new “speculative” tradition of building up a specialty; he works small and paints intimate and familiar subjects; he was not known in his time to a wider audience than the others. On another level he distinguishes himself from his contemporaries, producing a relatively few works overall, but works of such pristine perfection that they stand clearly apart.

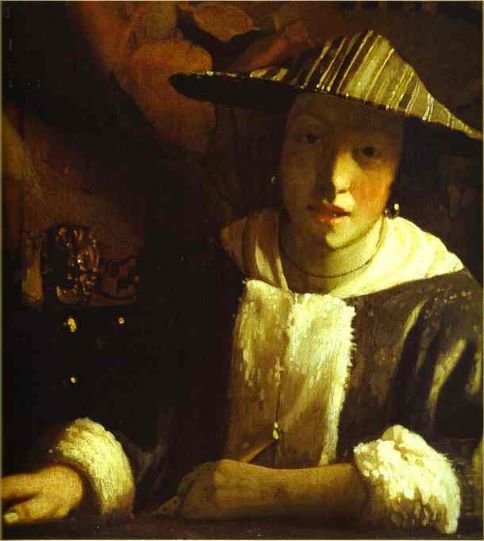

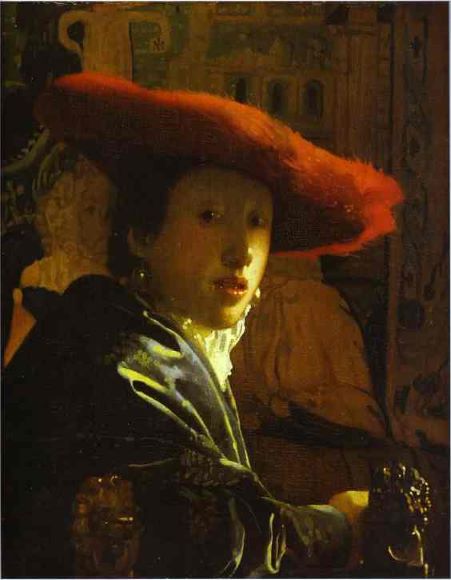

I fact, he sometimes works so small as to flirt with the boundaries of the miniature. He produced a handful of studies of women’s heads, a few inches on a side, but seeming somehow bigger than they are. Woman with a Flute is an excellent example. In its exquisite consistency of light from a single source, and its pearl-like droplets of paint, it gives evidence of Vermeer’s use of the camera obscura. This was a device which projected an image of what was in front of it on a surface, an ancestor of the film camera.

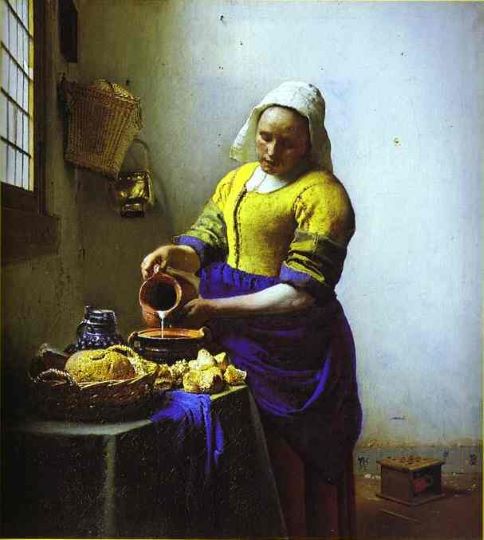

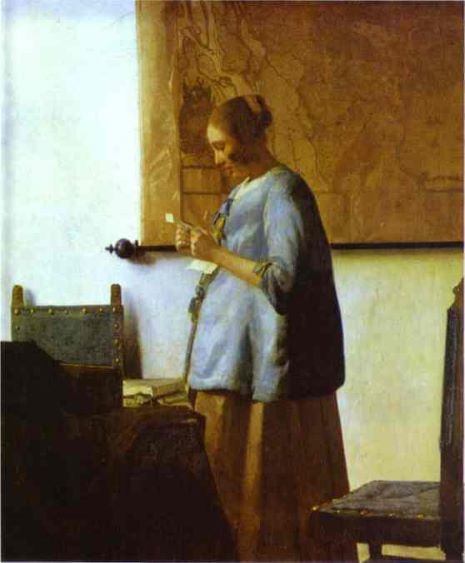

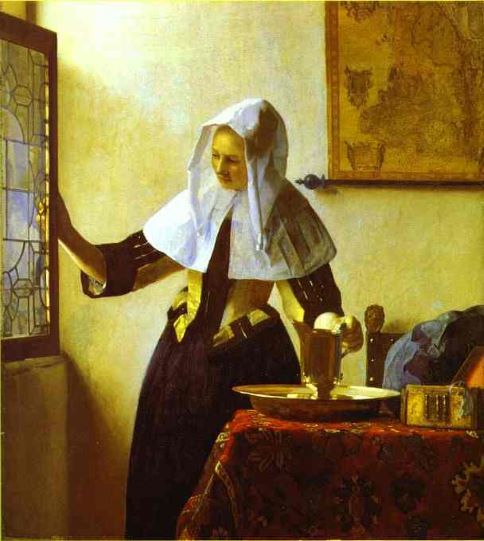

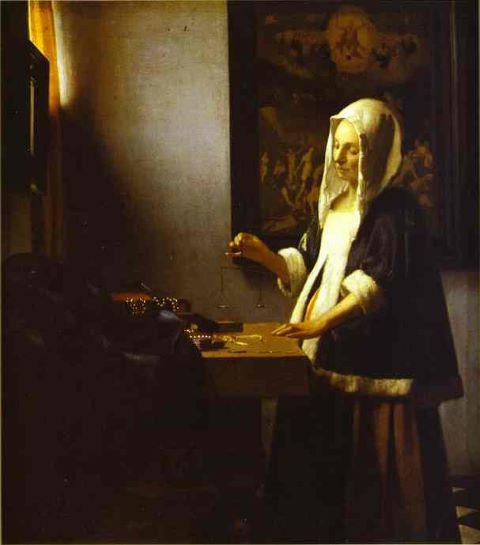

In his somewhat larger – though still small – interiors, we find the same complete control over the contents and light on a more ambitious level. The single source of light is always seen to the side of the frame or just outside it, and the light washes with utter consistency over everything it touches. The result is a timeless serenity which is remarkable, everything suspended, unchangeable, despite the momentary nature of the action. In many ways the works are more still lives than “action scenes”.

As we look at more of these interiors we find that we are always in the same space (the artist’s studio) with the same light from the same high windows, though the accessories change with each: a map, a painting, various furnishings. In every case the composition of objects on the surface, within the frame, is careful and completely controlled. The human figure is needed to complete the composition, much as a chalice might be in a still life composition. All is perfect, all is serene, all is timeless.

Though Vermeer’s oeuvre consists almost entirely of figures and interiors, I’ll finish with one lovely piece that is atypical, his “Street in Delft”, It shares with the interior scenes that still life quality of something carefully arranged, suspended at a perfect moment of balance. I compare it to a work which we saw in my last post, De Hooch’s “Courtyard in Delft”. The two artists share the same sense of order and balance, yet ultimately the de Hooch includes genre elements – elements of ordinary life – that Vermeer chooses to minimize. In the Vermeer the organization of the surface becomes its own reason for being. His closest spiritual affinity may be with the work of another Dutchman, Mondrian, three centuries later.