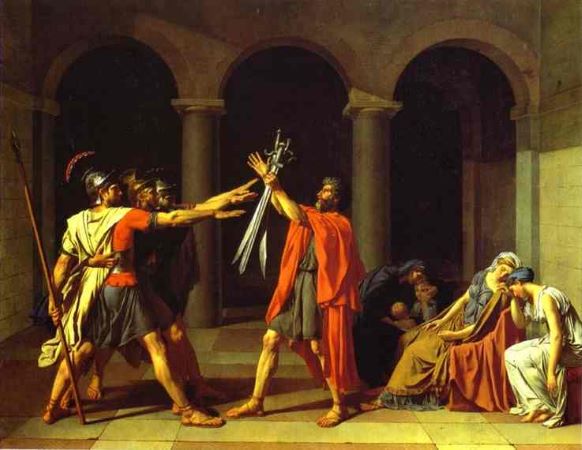

Jacques-Louis David and the “Oath of the Horatii”

It is almost impossible for us today to grasp the impact that a painting like David’s “Oath of the Horatii” had on his contemporaries on the eve of the French revolution. A contemporary writer claimed that this one painting had done more to promote the overthrow of the monarchy than all the revolutionary pamphlets of the period combined. It is all the more difficult to understand since, within a generation, David’s Neoclassical style had become “the establishment” against which younger artists were themselves struggling. Once colorism, or Romanticism, challenged the Davidian neoclassical standard, it became the new face of revolution. A good example is Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People”, depicting another revolution in a new revolutionary style.

No contemporary of David would have had the least trouble seeing the relevance of his work to the ideas of the time. To begin with, it is a subject drawn from Republican Rome, not from the Imperial period identified with the French monarchy. Secondly, its style was aggressively purged of the confectionary excesses of the Rococo art of the French court, represented here by Fragonard. Lastly, the specific subject of the Horatii spoke of revolution in the plainest terms to contemporary radicals.

The Horatii, three Roman brothers, have been chosen by the Senate to represent Rome in battle against the Curatii, three Alban brothers, to whom they were tied by bonds of marriage. In swearing to stand for Rome against their own family, they encourage Frech patriots everywhere to steel themselves to the pain of civil war.

“Les Horaces” (the Horatii) is a play by the 17th century French playwright Corneille, a play that was enjoying a huge revival in David’s time. David’s early sketches for the painting experiment with actual scenes from the play, but the moment he finally chooses to depict is not in the play, nor in any earlier accounts of the story. It is the perfect moment, more theatrical than any in Corneille’s play, the “pregnant moment” which tells of everything that has transpired and predicts everything to come. It was a staple of French theatre to reach such climaxes (they were called “tableaux”, or paintings) and to actually freeze at the moment of high drama to fix the image in the viewers’ minds. And, almost immediately after the exhibition of David’s work, a revolutionary playwright wrote a new version of the story, in which the culminating scene was David’s painting recreated on stage.

Thus, despite the fact that it is clothed in classical antiquity, David’s “Oath of the Horatii” is perhaps the most important revolutionary painting of all time, the “Guernica” of its day, and having immediate political effects far greater than Picasso’s masterpiece.