Let me start by admitting that Raphael is actually NOT one of my favorite artists; I am less into perfection than into tension and possibility. On the other hand, I would not feel good about leaving out the third of the triumvirate of Italian High Renaissance masters; fair is fair.

Raphael’s great achievement was to take the inventions of the prior generation of Italian artists (including notably Leonardo) and turn them into a canon which defines the High Renaissance moment. As we’ll see below, a key element of the canon was his depictions of the “Madonna and Child with St. John”, which were based on Leonardo’s “Madonna and Child with Ste. Anne”. First though let’s look at his most perfect fresco, the “School of Athens”. In it he achieves a resolution to the problem of putting figures into the newly developed perspective space .He limits them to the foreground space, but makes this logical by looking up at the background vaulted space from below.

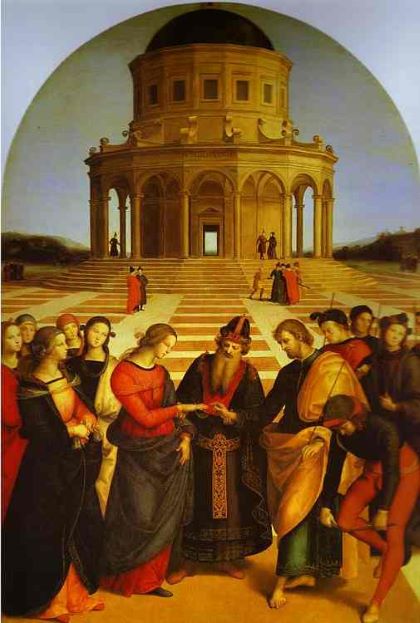

We can see the experimentation which led up to this resolution in Raphael’s earlier “Marriage of the Virgin”, and the still earlier “Madonna and Child” by Piero della Francesca. Each has become adept at creating a convincing space using the one-point perspective system, but neither feels confident enough to place his figures in it; instead, they are shown frieze-like in front of the space. The perspective system which had been developed so very recently works very well with architecture, but not so well with figures. We can define the “High Renaissance Moment” as the point at which all this experimentation led to a solution such as “School of Athens”.

As perfect a statement as this fresco is, it is not Raphael’s primary High Renaissance legacy: the resolution of the Madonna and Child canon begun by Leonardo da Vinci. I am showing two triumphant examples of the form, each with the timeless stability and serenity of the perfect statement. The pyramidal composition, the purity of the colors, the serenity of the figures, all proclaim the end of experimentation and the arrival at the goal.

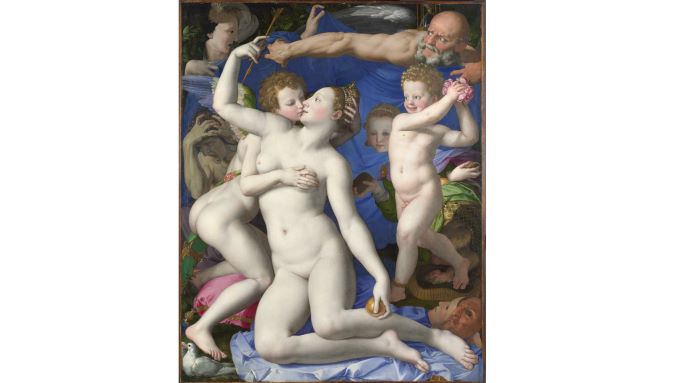

However, there is only two possible directions to go after perfection has been achieved: 1) repeat it with minor variations (many followers of Raphael did that), or 2) strike out in a new direction. Mannerism, represented by Parmigianino and Bronzino, sprang up almost immediately, since Raphael’s Canon left nothing more to explore. Both works shown below contain deliberate denials of the canon: distortion of figures, distortion of space, the abandonment of serenity in favor of ambiguity.

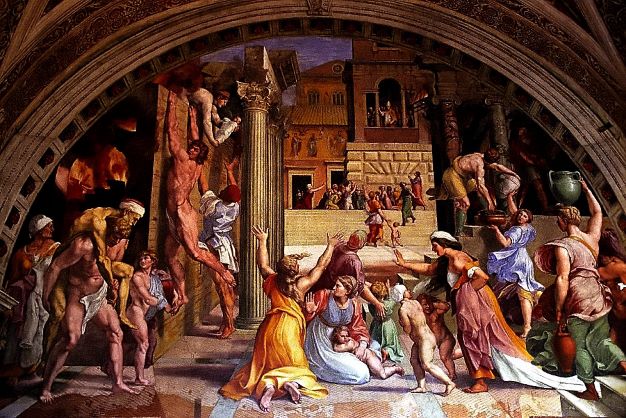

There are intriguing clues that Raphael himself would have pursued a Mannerist path, had he lived a longer life. In his late fresco “The Burning of the Borgo” he shows many mannerist characteristics in the handling of figures and space, and in the overall unsettled quality of the image. What would Raphael have become in these imagined “later years”? Is this a case where premature death has fixed our image of the artist at a moment when he is just beginning to define his direction?