With Rembrandt and Rubens a stone’s throw apart in Holland and Flanders, it is logical to pass now to Rubens. Calvinist Holland and Catholic Flanders were neighbors but were in other ways miles apart. Flanders was under the rule of the Spanish Hapsburgs, and very much a monarchy/aristocracy; Holland, though ruled by the House of Orange, was basically a merchant nation, ruled by the guilds.

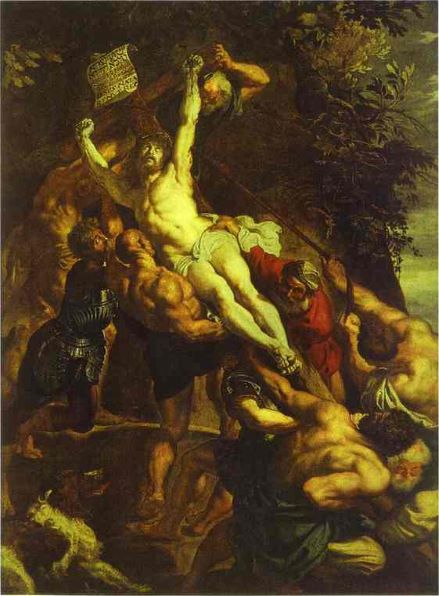

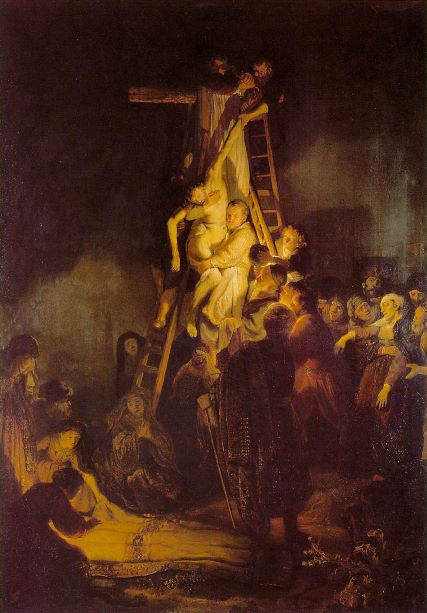

A comparison of religious works by the two great northern baroque masters highlights the difference in cultures, as well as their personal stylistic differences. Rubens’ “Raising of the Cross” is a display of tremendous weight, herculean strength and muscling-numbing strain, compounding each other to create a strong visceral impact. It reflects the bombast and pageantry with which Catholic ritual sought to clearly separate itself from protestant practice. When we look at Rembrandt’s “Descent from the Cross”, there is some weight and strain, but all in service of a more spiritual meaning. Each person participating has his/her own personal relationship to the event. Furthermore, in contrast to the dramatic moment shown in the Rubens, emphasized by the long diagonal of the composition, the action and vertical composition in Rembrandt’s work seems suspended in time, drawing you to contemplation of the event’s deeper significance.

Two more works show Rubens’ genius in developing new dynamic compositional patterns. The” Madonna Enthroned” (a sketch for a large work to be executed mostly by his assistants) exhibits an upward spiral movement, reinforced by the staircase, and culminating in the figure of Mary being crowned. Splendor, awe and majesty are the messages. Anyone looking for a personal connection to deity need not apply. The other work, “The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus”, show another compositional invention, a pinwheel or whirlpool of potion around the central figures. And as in “the raising of the cross”, weight and strain add greatly to the tension communicated by the piece. A stroke of genius is seen in the slender gap between the figures of the two daughters, where the tension becomes excruciating.

Given our current taste in feminine beauty – slender and petite – we are likely to find Rubens taste in women faintly ridiculous, or even disgusting. You can be sure he would have felt the same about our sex icons. The three graces totally lack a feeling of what we now think of as grace. But we can agree that they are supremely tactile, appealing vicariously to the sense of touch as much as to vision. A similar taste is seen in the water nymphs in “The Landing of Marie de Medici”. This is one of twelve gigantic paintings commissioned for the wedding of Marie to Phillip of Navarre, who here is seeing her for the first time. Though much of this painting and its eleven pendant pieces would have been painted by an army of apprentices, Rubens would have saved the painting of the nudes for himself.

I finish with a piece which Rubens clearly did for his own pleasure, one of several similar hunt scenes. Nothing expresses his artistic vision better than this insane swirl of activity – a pinwheel even more violent than in the “Daughters of Leucippus” – enriched with extreme action and violent color. It is like looking into the mouth of a volcano. The color and emotion were an inspiration to Romantic painters like Delacroix two centuries later.

Fantastic! The painting of the Hippo Hunt really captures the chaos and the aggression.

Yes; this is one of several he did with variations of this theme. The composition is the very definition of “maelstrom”.