Finding Needles in the Haystack of Nature

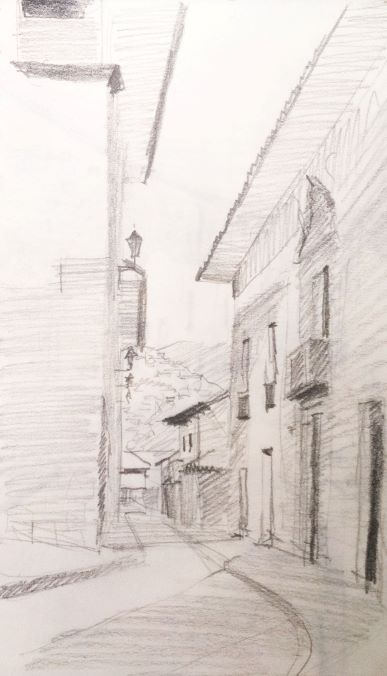

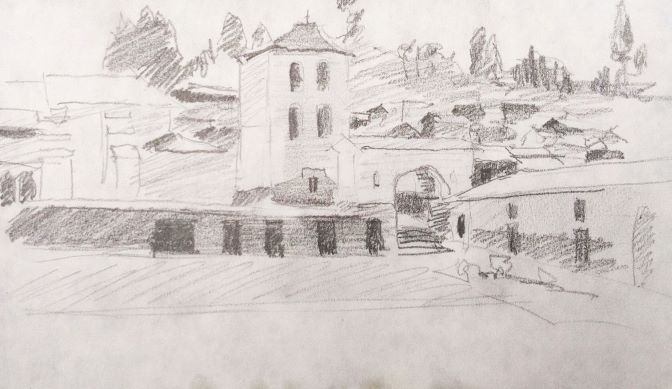

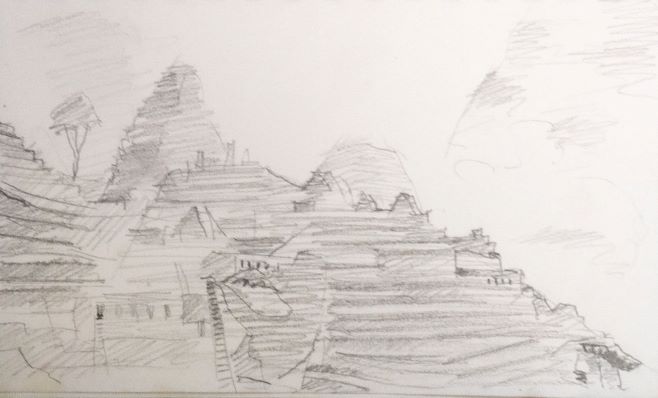

When working from nature on a two-dimensional surface, it is fair to say that the translation of three dimensions to two is the fundamental underlying task you face. This assumes that you want to reflect your experience of the three-dimensional world; if you don’t you can skip this whole section. There are many ways to create an illusion of spaces and distance on the surface: converging lines, a progression in size of like objects, going from high contrast and saturation of color for the foreground, to low contract and saturation in the distance, using narrative clues. When you look at a scene, there are many times when it is not obvious how best to recreated spatial relationships successfully. My mantra is simple: nature encompasses everything, including what you need to reach your goal. In other words, there is no need to invent, only to select.

When I teach painting from life – any subject – I always describe it as “eye training”. Though there are some other specific skills or tricks to teach, I am convinced that 90% of the work I do when painting happens in the eye. When I go to comment on a student’s efforts, one thing I will say is “I see a reflected light coming into that area of shadow; do you see it?” I am guiding their eye to learn to see more. What they choose to use depends on their personal vision. Some of us see in shapes and lines, others in color fields, still others in light and dark.

If you are interested in effect of light, your eye will already be training itself to see them. When you begin to try to capture these effects, you will be forced to a whole new level of seeing. What is true of light is equally true of form and color. This heightened level of seeing takes time to develop, and can atrophy quickly. If you get away from your enterprise for as little as a month, there will be some stretching to get back to where you were. One of the best pieces of advice an artist can get is to carry a sketchbook everywhere and never stop filling it up.

So aside from telling you to look more intensely, what can I tell you to help you see what you need? I already described the “finger frame” in an earlier post on framing; you can also use a “finger ruler” to help determine the relative size of things. Hold up a pencil or brush handle vertically at arms length, put the tip at the top of what you are measuring and your thumbnail at the bottom. You can then transfer this measurement to any other part of the visual field to see if it is longer or shorter and by how much. Be sure to keep your arm straight and pencil vertical!

Another trick is to draw a central vertical and horizontal faintly on your panel, dividing it into quadrants. What part of the visual field falls into each quadrant; what is in the center? Another trick is to determine the size of each object or area by reference to its neighbors. Where does the top of the building reach against the trees beside it? Of course, once you eye is in, such crutches aren’t needed.

But enough of tricks. These aids are cumbersome in the extreme when compared with the ability of the eye to see exquisite detail, subtle gradations, and tiny nuances. These are what you need to create a convincing illusion of space on a flat surface, one that has truth, freshness and immediacy.