Cornering the Will-o-the-Wisp

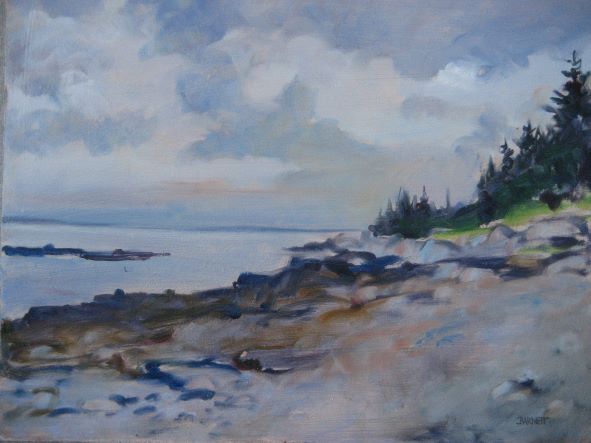

In an earlier post, about why I am out here in the sun, rain and snow, I said that the primary reason was because my painting enterprise is all about capturing a moment in light and color, with freshness and truth. This is why I prefer a high overcast day, with steady ambient light, giving me breathing space to record what I need. The advantage of such days is not only the time available before everything changes, but also the quality of colors. In bright sunlight all but the strongest of colors are washes out. While sunlight gives you two or three greens, an overcast day gives you fifty.

Of course, as Turner knew, the most magical moments in nature are at dawn and dusk, when everything changes right before your eyes. Thanks to the camera, we can choose to deal with these subjects second-hand…but it is not the same as being there! When staying on the Florida shore, I resolved that I would capture the dawn as it happened. First, I timed it the day before. Then, I got out there ten minutes ahead to block in my view before the moment I really wanted to capture. Another wonderful time is when broken clouds dapple the ground with shifting patterns of light: wonderful but frustrating. You are constantly saying to yourself “do I keep what I just saw, or change to what I now see?”

The bottom line is that, if you want to corner the will-o-the-wisp, you must be ready, be intensely focused, and be FAST. The huge side benefit is that, once mastered, that speed will be with you for any subject: portrait, landscape, still life, figures. I allow myself 30 seconds to establish the major reference lines of the composition (the horizon is a good one!), going from side to side and top to bottom. I give myself only ten minutes to complete the reference drawing: identifying all the elements, their size and shape, and their relationship to each other. After ten minutes, YOU SHOULD BE AT PHASE 2: BLOCKING IN THE COLOR MASSES. Some complex subjects take longer.

The key to speed is to replace description with suggestion. The reference lines do not need to be ”right”; they won’t be present in the final work .In phase 2, as you block in the color areas, You need not take account of all the subtle variations within them; that will come later. And if you apply the color with strokes that also describe edges and suggest texture, you will have accomplished three things at once. Do your foliage with a “foliage stroke” and your grass with a “grass stroke”.

What you notice immediately as you focus on the light and color of the moment, particularly if you are looking at clouds, is that they are changing constantly as you look. One is constantly faced with the choice: do I prefer what I saw just then, or what I am seeing now. My default assumption is that I will hurry to fix on the panel the light and color that was there as I started and ignore later changes…but very often what was good becomes better and I grab it. The trick is not to let two versions of “now” coexist when you’re done.

When talking about my reasons for painting direct from nature, I said that my goal, my painting enterprise, is to look at an oil sketch when it is done and be able to say: “I got it! That is the way the light and color was in this place at that moment!’ This is truly my greatest satisfaction in painting, and the beauty is that, looking at one of my successes, I can always recapture the feeling.